My grandma patiently waited as I swiped through photos on my phone to find a picture of my friend’s new baby. A proud ‘auntie’ in my own right, I was absorbed in the search when my grandma asked, “Why are there so many pictures of words?” It was true; we had swiped past zoomed-in photos, capturing slightly blurry sentences from the book I had been reading. “I needed to keep the sentence; it was too beautiful.” My grandma, a collector herself, didn’t question it other than to ask what I did with these snippets. Other than occasionally, send them to a friend who might appreciate them. They mostly died right there in my photos.

I couldn’t explain to my grandma why I loved these sentences. Why did they demand to be saved? If I ever wanted to craft sentences like the ones I loved, I needed to understand what made them stand apart. These are the four steps that I took to improve my writing by reading what I loved.

Step 1 – Slow down (just a little)

The book community, especially Booktok, has been confronting the policing of reading speeds. Read as quickly or slowly as you want, but if you are reading to improve your line-level writing, slow down just enough to grab a pen or highlighter or drag a finger across your e-reader – you will need to annotate.

Step 2 – Annotate

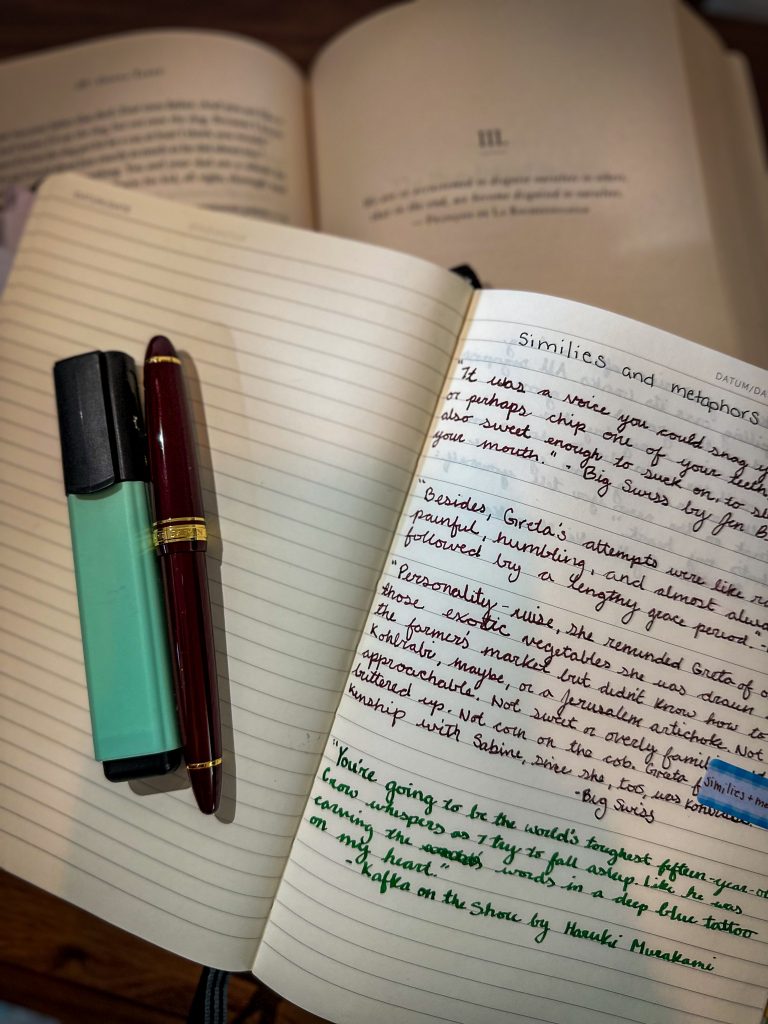

I took pictures because I was afraid of marring a book. I practically worshiped books; the idea of defiling them seemed a crime worthy of the severest punishment. Eventually, I started to see annotations for the loving appreciation that they were. If you feel uncomfortable writing in your books, ease your way in. Start with sticky notes (like these clear ones on Amazon) and place a tab on the page so you can return to your notes. Now, my books are beautifully tabbed, highlighted, and underlined with notes in the margins. (Side note: Some of my copies of books are too beautiful for me to annotate in them, so I have two copies of the book. Or if it is a library book, I copy out the sentences into a notebook and sort through my favorites at the end.)

Step 3 – But what are you noting?

Look for sentences that stand out for their honesty, beauty, or a reason you can’t immediately understand. Dig into these sentences.

- Ask yourself – why did I stop at this sentence? Is it so good that it brought me to a stop? Or has it distracted me and pulled me from the story?

- If the sentence is a distraction, what pulled you out of the story? Is the tone off in comparison with the rest of the passage? Is the writing self-important? Drawing attention only to itself? How can I recognize this and avoid it in my writing?

- If the sentence caught your attention for a positive reason, what is it? What work is the sentence doing? According to Kurt Vonnegut, “Every sentence must do one of two things—reveal character or advance the action.” Can you identify the purpose of the sentence?

- Read the sentence aloud; how does the rhythm of the sentence work?

- Is the writer using any specific techniques to enhance the sentence?

Possible techniques

- Metaphor/Simile – A metaphor or simile compares two unlike things. You probably learned to use them in grade school. They are nearly everywhere, and I can bet you already use them in your writing, but there is the danger of falling into cliché. She is as sweet as sugar. Strong metaphors evoke the senses and are often expanded.

Examples:

It was supposed to be spring; down in the small garden by the bank’s entrance, the crocuses were blooming. But it had snowed earlier that morning, and the bowl of each small flower brimmed with a foam of snowflakes, like tiny cups of cappuccino.

People of the Book by Geraldine Brooks

Your heart is like a great river after a long spell of rain, spilling over its banks. All signposts that once stood on the ground are gone, inundated, and carried away by the rush of water. And still, the rain beats down on the surface of the river. Every time you see a flood like that on the news, you tell yourself: that’s it. That’s my heart.

Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami

- Rule of Three – Humans love patterns, and three is the smallest unit capable of being a pattern. You’ll find the rule of three just about everywhere you look: structure (3-Act Structure), Characters (Three Little Pigs), and at the line level.

Examples:

She would transform into the wealthy ranchero’s daughter she was meant to be when she met these suitors: obliging, ornamental, obedient.

– Vampires of El Norte by Isabella Cañas

Besides, Greta’s attempts were like root canals – painful, humbling, and almost always followed by a lengthy grace period.

Big Swiss by Jen Beagin

- Finding the exact right word – When writing, we should always search for the right word. This often means turning to the dictionary to double-check the meaning of a word that you are positive you know the meaning for, but it can also mean searching for the unexpected word that says exactly what you mean.

Examples:

It’s not that I’m unaware of the suffering and the soon-to-be-more suffering in the world, it’s that I know the suffering exists beside wet grass and a bright blue sky recently scrubbed by rain.

Tom Lake by Ann Patchett

It was a fine afternoon, but the cold sunshine beyond her office window oppressed her.

The Weight of Ink by Rachel Kadish

- Specificity – You’ve heard it before, show don’t tell; it’s generally good advice, but it’s a tool, not a rule (read more here). Specificity is showing and showing in detail, leaning into the part of the whole.

Examples:

Snow blanketed every rooftop and weighed down on the branches of the stunted mulberry trees that lined our street. Overnight, snow had nudged its way into every crack and gutter.

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

She had agonized about what to wear, tried on and discarded nine outfits before she decided on a teal dress that made her waist look small.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

- Other – Spend time with the sentences you love. What makes it appealing to you? Read it out loud – is it the rhythm of the sentence? Is the author anthropomorphizing? Or using alliteration? Something else?

Step 4 – Keep a record.

Create a record of the writing that you love the most; It can be a journal, a document on your computer, or a note on your phone. Mark what you love about the quote and what you notice that the author has done to make this sentence shine. All the example sentences above were pulled from my notebook. They are sentences that stuck out to me because I noticed the craft of the author.

By paying attention to why I love a sentence, I’ve been able to implement more of the techniques that I appreciate into my writing. My phone is no longer filled with random pictures of sentences, and instead, I have a notebook that I can turn to when I want to think about what makes writing stand out to me at the line level.

- Harlem Rhapsody by Victoria Christopher Murray - December 4, 2025

- “The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree” by India Hayford - May 15, 2025

- “Soft Burial” by Fang Fang - April 24, 2025

Sign up to our newsletter to receive new articles and events.