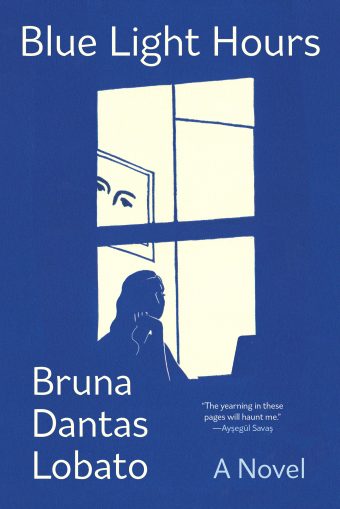

We’ve all been there – sitting in the blue glow of the screen that holds the image of the loved one we would do anything to have in our arms. Blue Light Hours by Bruna Dantas Lobato is a novel about that unique brand of loneliness. A young woman from Brazil leaves her home and starts college in a remote Vermont town, leaving behind her single mother. The two women cling to each other through their nightly Skype calls as each learns to navigate life independently.

This novel is a meditation on love, loneliness, and obligations between mothers and daughters. It is for readers who enjoy slow, reflective character studies. This novel felt personal as an only daughter who moved away from home. Are you responsible for the well-being of your loved ones? Are you free to create the life you dream of? Are you even allowed to dream?

The writing is beautiful and sharp, creating a yearning that lingers long after you’ve stopped reading. Thank you, NetGalley and Grove Atlantic, for providing an advanced copy for review consideration; all opinions are my own.

For writers who want to learn more, Bruna Dantas Lobato offers lessons on writing in the white space and balancing showing and telling. (See Michael’s article for more on why “show, don’t tell” is a tool, not a rule.) The writing is spare and never overly emotional, yet the story’s feelings and emotionality linger with the reader.

“I lived alone, I rarely spoke, I ate badly.”

This sentence sits alone, sectioned out from the rest of the page. Its brevity is its representation of pain. We don’t need to see our main character shuffling around campus or surviving on ice cream from the dining hall. We know that she is suffering, that life is hard, that she doesn’t have the energy or willpower to get into the details of it for us – and in that, we find her pain.

“A boy seemed interesting one night in the library, in dim lighting, past our bedtimes, and I smiled too much and talked too fast, but then he said, I love your accent, I love how you say that word, and I never talked to him again.”

In Michael’s article, he talks about knowing if you need to show or tell based on the purpose of the sentence. This little vignette happens as she tries to think of something to tell her mother about her life. We could see this whole scene played out, the boy sipping coffee as she babbles about something, only to have him ignore what she is saying for how she says it. We could see her leave and feel disappointed, but we don’t need to. The purpose of the sentence is to show that it happens and that it isn’t great but also that it isn’t worth mentioning. The purpose of the sentence is to tell us this, and that’s precisely what it does.

“I walked over to the window with my computer and I saw my own face and the glowing screen reflected in the windowpanes. The shards of ice rushed past us, slicing through the air.

I tapped at the glass.”

One of my favorite aspects of the novel is how the author shows us the distance between mother and daughter. She does this by showing the screen that connects and separates them. Here – their reflections are together in the windowpane, yet it is a facsimile of togetherness. Only the daughter can reach out and tap the glass.

- Harlem Rhapsody by Victoria Christopher Murray - December 4, 2025

- “The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree” by India Hayford - May 15, 2025

- “Soft Burial” by Fang Fang - April 24, 2025

Sign up to our newsletter to receive new articles and events.