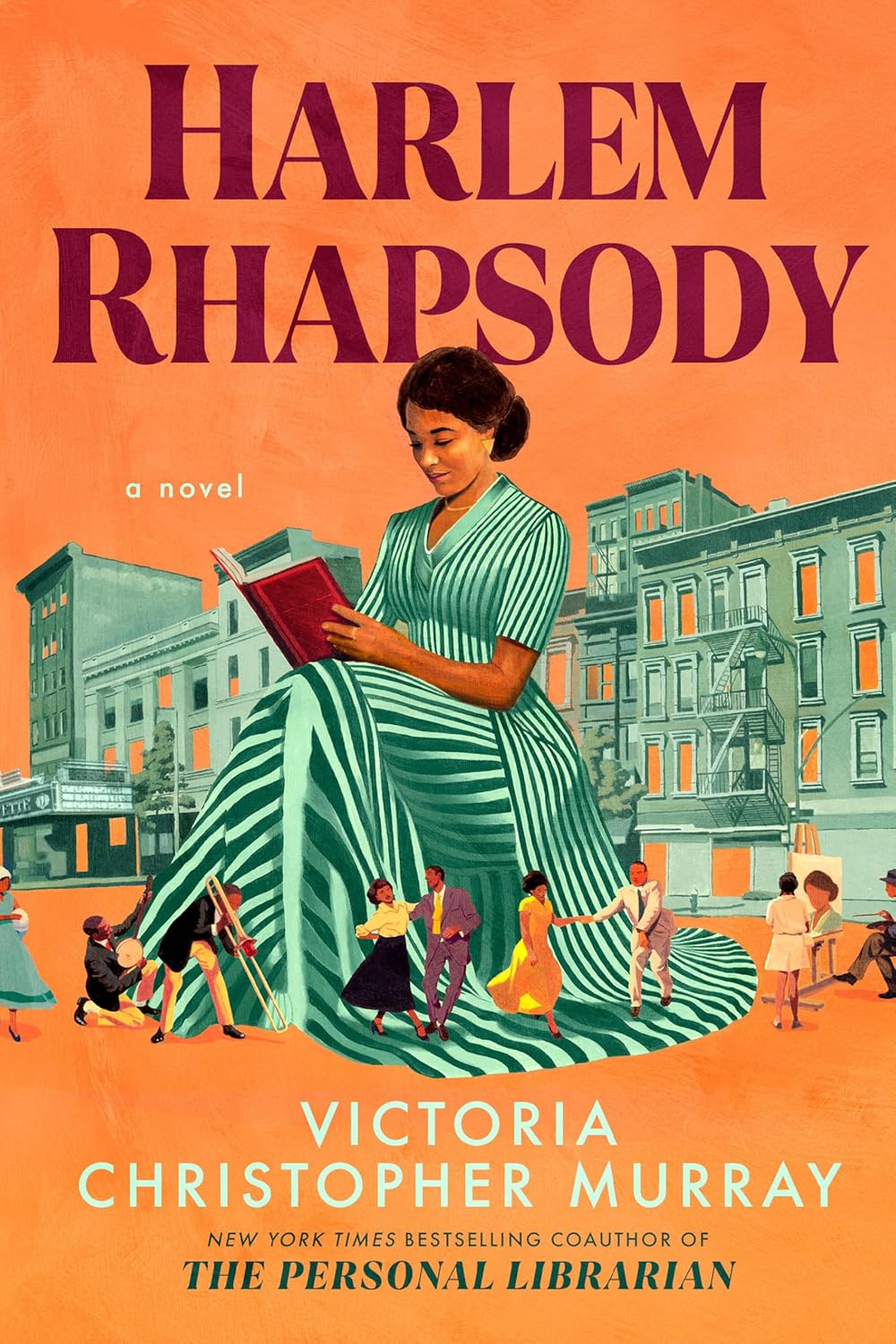

Jessie Redmond Fauset has just arrived in New York City to become the first Black female literary editor. A talented writer, graduate of Cornell, and member of Phi Beta Kappa, she is ready to make her impact at The Crisis—the premier magazine for Black Americans. The only problem is the pesky (true) rumors about her relationship with the married founder of the magazine, W.E.B. Du Bois. Determined to prove her abilities, she pours herself into mentoring her writers. Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Nella Larsen, and others thrive under her careful edits and passionate attention. Hughes will eventually call her the “midwife” of the Harlem Renaissance literary movement.

Victoria Christopher Murray does a beautiful job of placing the reader among the heroes of the Harlem Renaissance as they grow into that status. It is enchanting to see the impact of one woman on an entire movement. Murray does a great service in bringing Jessie back into the spotlight, even if the relationship with Dr. Du Bois can become tedious at times.

For readers wanting to learn more about writing, Victoria Christopher Murray’s Harlem Rhapsody does an excellent job of blending truth and fiction. It seems to be a nearly universal trait among historical fiction writers to struggle with this balance. When the novel involves real people, especially beloved historical figures, the obligation to truth becomes even messier. Murray deliberately chooses to go against the facts, even going so far as to change the timeline of Langston Hughes’ life, inserting him in New York when he was actually living abroad.

At the end of the book, Murray’s historical note delves into her research, her desire to stay true to the facts, and her rationale for changing them. This provides an opportunity to imagine the book without those changes and to determine what is gained or lost by her decisions. Do they make for a more compelling story? By changing the strictly historical facts, is a deeper truth revealed? Is it possible to tell the full story without Langston Hughes?

- Harlem Rhapsody by Victoria Christopher Murray - December 4, 2025

- “The Song of the Blue Bottle Tree” by India Hayford - May 15, 2025

- “Soft Burial” by Fang Fang - April 24, 2025

Sign up to our newsletter to receive new articles and events.