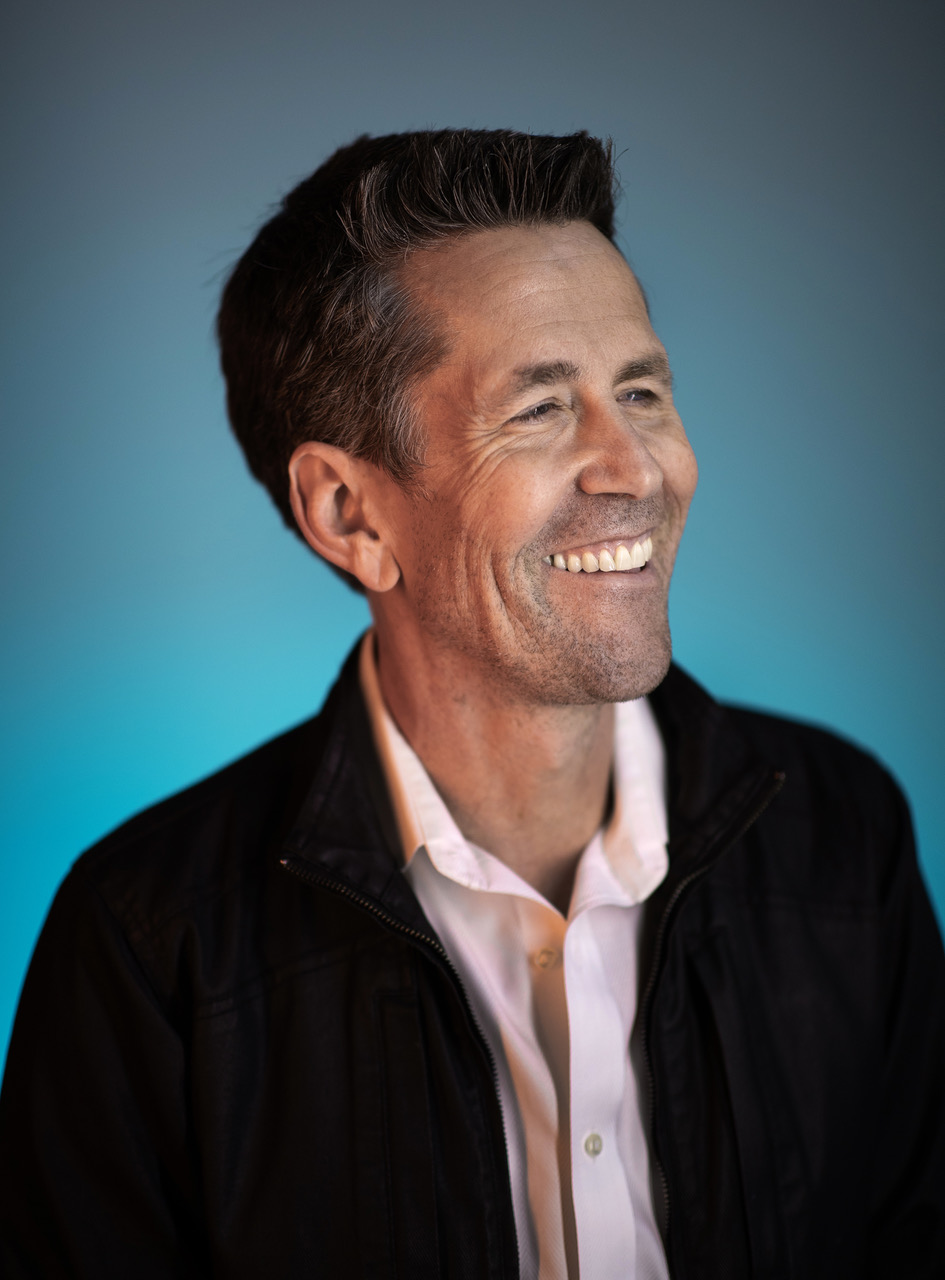

Jess Walter is the author of eleven books that include a #1 New York Times best-seller (Beautiful Ruins), an Edgar Award winner (Citizen Vince), a finalist for the National Book Award (The Zero), and an NEA Big Read (The Cold Millions). His short fiction, published in two collections, has won O. Henry and Pushcart prizes and appeared three times in Best American Short Stories.

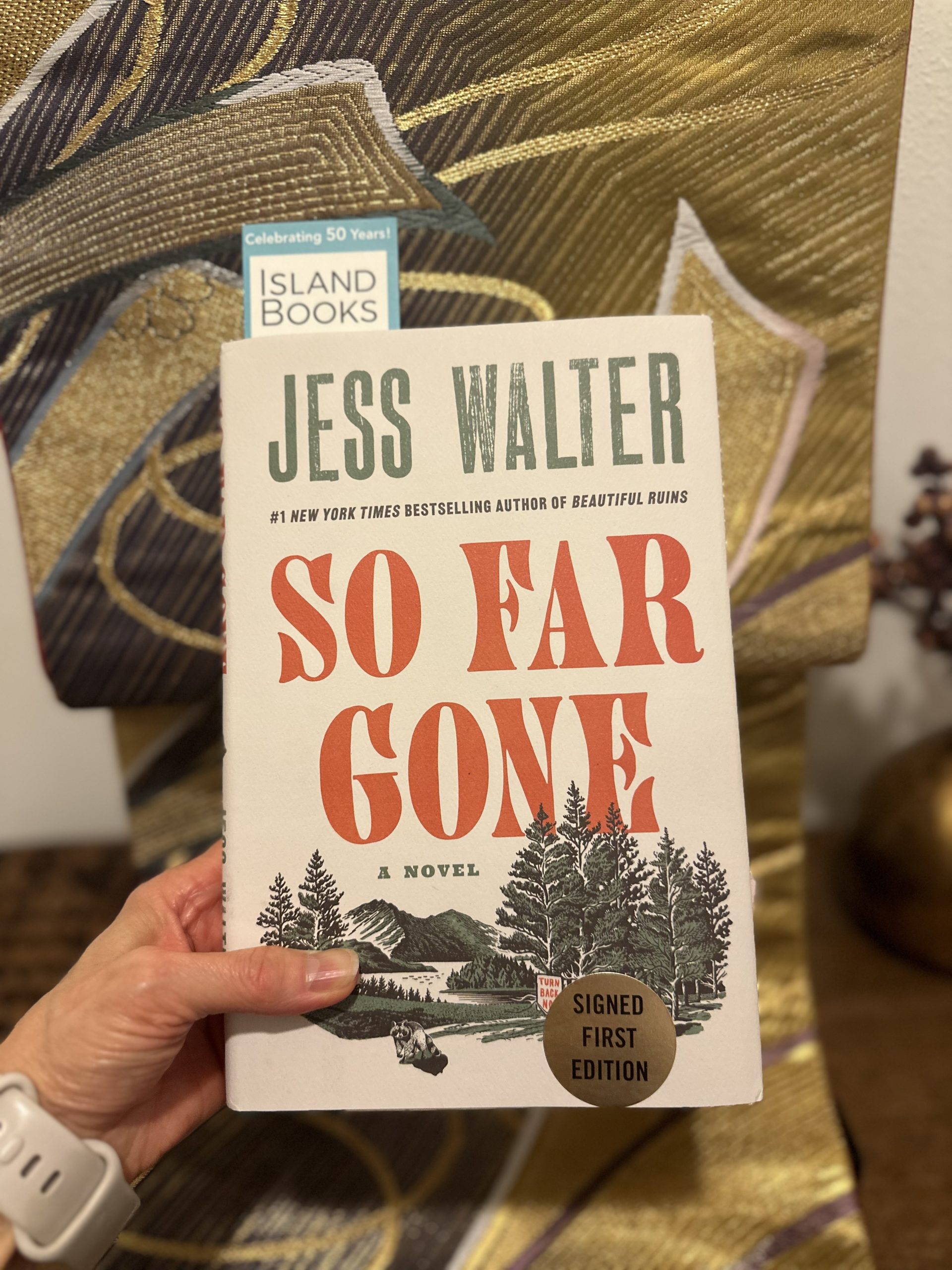

Jess, thank you for allowing me to interview you on behalf of Story Street Writers. I’d really like to expose our readers, who are mostly writers, to your incredible storytelling and writing talents. I’d also like to congratulate you on all the enthusiastic buzz around your recently released novel So Far Gone. I personally thought the book was an awesome combination of hilarity, poignancy, vulnerability, memorable characters, and important political and social issues—all presented in peerless prose with finesse and grace.

By the way, I loved Lucy Park and the way you portrayed her brash, strong, but compassionate personality. It is rare to see a half-Asian woman main character in a novel written by an author who is not a half-Asian woman. And this sounds so cliché, but it made me feel seen. I’m curious about why you decided to make Lucy Park mixed race.

JW: My approach to writing characters outside my ethnicity, outside my gender, outside my experiences, is pretty simple. I just try to reflect the world as it exists: diverse and rich with people who look, think, and act in their own unique ways. From all sorts of backgrounds. I understand the hesitancy to write outside one’s ethnic identity. Self-doubt can creep in. (What if I get something wrong? What if I’m unintentionally offensive?) That can, ironically, cause writers to create characters who lack depth, who don’t act selfishly or stupidly, or with ill intent. But if we were to only write people like us, our fictional worlds would be pretty thin—I always think of the movie Being John Malkovich, where the whole world is full of only John Malkoviches. So I try to write characters whose human attributes (desires, failings, ambitions, fears) override their differences in background, experience, race, and religion. I try to be respectful to those differences, of course, but more important to me is reflecting the complex natures of all people. Simplicity is, to me, the most offensive character trait.

With Lucy, her ethnicity felt secondary to her career at this point in her life. Working in a newsroom, especially around cops, often gives a person both a dark sense of humor and a knack for profanity. Cops will take advantage of any perceived weakness or innocence. That was Lucy for me: smart and funny, but has learned to take no shit from anyone; in fact, she has such an incredibly sharp tongue that she can sometimes seem tactless. No walk in the park, for either Kinnick or Chuck, dating someone quick to the harshest truth. That led me to the name Lucy Park, and I liked the name so much then I began imagining this diminutive Korean-American woman. Throughout life, people probably assume her to be a certain way based on her size and their own biases, and she’s one of those people who likes to puncture expectations, so, as a reporter, she grows into this woman who happily tells people to go fuck themselves into a hole (if they deserve it 🙂 .)

~*~*~*~

You are a popular man. The publishing industry seems to adore you (I saw the Ann Patchett reel), and you have a large, loyal base of reading fans. I’ve seen you present multiple times. You charm and entertain. Nobody walks away bored or unimpressed.

JW: Thank you, Margaret. I promise I have bored and unimpressed in equal measure over the years.

How much do you think your popularity and ability to engage audiences help to build your reader base?

JW: Funny how a word like “popularity” takes one right back to middle school. And just like middle school, I suspect the more time you spend worrying about things like popularity, the less interesting and authentic you become. And since popularity (like book sales) is out of your control anyway, I don’t think about it.

Just write and read and write and read; that’s all you can do. Everything you need to create beautiful work is right there at your fingertips every day: the letters used to make the words used to make the sentences used to make the stories used to make, hopefully, something artful and meaningful. That’s what people react to: art and meaning. The rest is just you preening in front of a mirror, still fourteen, wondering when your complexion is going to clear up.

~*~*~*~

Let’s talk a little about your history. You began your writing career in 1987 as a reporter for your hometown newspaper, The Spokesman-Review. Your books often seem to have required a great deal of research. As a former journalist, you must have initially developed these skills during your newspaper days. I’m guessing you enjoy research and its educational value, even if you don’t use half of what you uncover.

Please discuss your feelings about research, a little about your process, and offer any research tips or advice you’d like to share with other writers, especially emerging ones.

JW: Another word for research, for the fiction writer, is obsession. It’s wonderful to become obsessed with the subject you’re writing, to read every book you can get your hands on, to go to the places you’re writing about and try the food, interview people, breathe the air, live in the time and place where your story is set. When I was writing about Italy in the 1960s, besides taking a couple of trips there, I also loved watching old Italian films. Two years after Beautiful Ruins was done, I was still watching Fellini, De Sica, and Antonioni movies. Later, another story, The Angel of Rome, came out of that obsessiveness. Relish the obsession.

One tip I would give is to make use of an old resource: the public library. The problem with internet research is that it tends to narrow your research. You look for only the thing you’ve already imagined you need, and it closes the loop. (Q: What size engine did the 1964 Impala have in it? A: The 230 cubic inch to the 409.) But open the old newspaper microfilm in a good library to October 11, 1964, and you are flooded with not just the answer to that question but with more questions. Okay, here’s an ad for a ’64 Impala with a 409. How much did it cost? $2,750. And look, what movies were playing in 1964? (Dean Martin in Kiss Me Stupid) And hey, here’s a clothing ad from a wedding shop, how much was a wedding dress? (Maybe I should have my characters plan a wedding. An outdoor wedding. Where they drive their convertible Impala. Only, look, the wedding gets postponed, and the car is ruined, because there was a crazy hailstorm on October 11, 1964. Three horses died in the hailstorm. And the bride is angry that the groom is sadder about his car than the postponed wedding. Wait, why are they getting married in the fall? Is there a baby? Where are the birth announcements in this paper? What were the babies named? Linda? Oh my, yes, their baby is named Linda!)

~*~*~*~

Before you wrote your first book, Ruby Ridge (1995) originally released as Every Knee Shall Bow, you were part of a team named as a 1992 Pulitzer Prize finalist for coverage of the Ruby Ridge shoot-out and standoff in Northern Idaho. It must have felt incredible to receive that honor.

Was it the Pulitzer nomination that inspired you to take that reporting experience and author your first book? Did you continue to work as a journalist while writing that first book?

JW: I did continue to work as a journalist, for two years after the Ruby Ridge standoff. I took a couple of month-long sabbaticals to work on the book proposal and on the book itself, and I kept covering the case, writing about the trial and the various investigations after the events of 1992. The desire to write the book had nothing to do with whether or not we won the Pulitzer. (We did not, the LA Times won, for its coverage of the Rodney King riots.) From the minute I arrived in the woods, at the standoff between the federal government and Randy Weaver’s family, I wanted to write a book about it, to understand it, and to try to explain it to others. In 1993, I got an agent, but he couldn’t sell the book, and he ended up quitting and going off to become a teacher. So, I started sending the book proposal to editors on my own. When Judith Regan at HarperCollins finally bought the book, I had to negotiate my own book deal because I no longer had an agent. I negotiated my first three book contracts before I finally got smart and found someone to do that part of the job.

At what point in your book-writing career did you feel comfortable leaving full-time employment as a reporter to devote yourself to writing novels?

JW: My first book was published when I was 29 and that’s when I left my newspaper job. That’s technically the last “job” I had. (Once, recently, my daughter asked for advice on applying for jobs and after I said something stupid like—just fax them your resume—she said, “Wait, when did you last apply for a job?”)

I did have to take some ghost-writing assignments early on, to keep my kids in food and college, but I didn’t like doing that. My first novel was published when I was 34. I’ve always done other things—teaching, writing screenplays, giving speeches—in part to support my family and in part, because it makes for a richer life. I was probably in my mid-40s before fiction started paying a larger share of the bills than various other random jobs I did. But I had devoted myself to writing fiction well before that. It was always the most important thing to me, next to my family. Every day, every week, every year, I wrote fiction, at night when my kids were little, and then, when they were older and could dress and feed themselves, first thing in the morning. Every other job I did was in service of writing fiction.

~*~*~*~

One of the first things that impressed me about you as a writer is your practice of writing across genres or categories. Picking up a Jess Walter book is like opening an Advent Calendar door. You’re never sure what’s going to be inside, but you know you are going to enjoy it. After writing a nonfiction book, what prompted you to venture into fiction and write your first novel, Over Tumbled Graves?

JW: I had always wanted to be a fiction writer. I became a father at 19, as a college sophomore, and so I ventured into journalism as a way to support a young family while learning to write. I loved journalism, too, and consider it the best training ground I could’ve had to become a fiction writer. I was honing my craft—reading and writing fiction and sending out short stories—throughout my journalism career, and after my first nonfiction book was published. I think, every step of the way, I’ve tried to do, in my own way, a version of what Toni Morrison advised: Write the next book you want to read. It’s really as simple as that. I write across genres because different stories have different requirements.

How would you say your writing has evolved since publishing your first novel?

JW: Hopefully, my writing has evolved in every way and in every possible direction. Being an autodidact, having no MFA and having taken no classes or workshops in fiction writing, my early attempts at writing fiction were geared toward simply teaching myself how to do it. I sent out short stories for seven years before I got my first one published. My first novel, published in 2000, had 54 chapters and was broken into very small sections, in part because those small sections were about as long as I could sustain my belief in myself as a fiction writer. I think of those chapters as scaffolding, and I needed a lot of scaffolding to construct a whole novel. I read nonstop through my 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s (I just turned 60), and the combination of constant reading and writing made me far more confident as a writer, and much less reliant on things like structural scaffolding. The Zero, which came out in 2006, had only three chapters. By the time I published Beautiful Ruins in 2012, I didn’t feel constrained by chronology, or point-of-view, or verb tense, or any other element of fiction writing. By that time, it had all begun to feel like glorious, inventive play, and I couldn’t wait to try something new every time I sat down to write.

What are your story development and revision processes like?

JW: Different every time, I suppose, and dependent on what I’m writing. My novels have taken me anywhere from one year to fifteen years to write, so it’s hard to say there is one kind of process at work. But I am a chronic reviser (except when I’m answering Q-and-A’s, so I apologize for any sloppiness.) One constant is the reading of my work aloud to make sure it sounds right. I spend far more time on the sound of what I’m writing than on thinking about what happens next. When I do think about the elements of the story, I tend to think of them in terms of shape; what is the shape of the narrative I’m working on? I like to imagine a shape as pleasing as the rhythm of a great sentence or paragraph. As powerful as a perfect line of poetry.

Imagine you are facing a class of emerging writers. What three pieces of advice would you give them?

JW: Oof, I have faced that class, more than a few times. And it’s daunting. Everyone is starting from a different place, imagining a different destination. That student over there is thinking (I want to write a best-selling dystopian series that makes people finally understand what a misogynistic world we live in.) This student over here is thinking (I want to write lines that make people close their eyes and contemplate their own mortality.) Another student is thinking (I just want my ex- to see that all the time I spent on this bullshit has finally paid off with a published book.) What could one say that would match all of those deeply-held ambitions?

First, of all, read more. There is no kind of writing that exists without its practitioner being a voracious reader. (And if there is, I’d want nothing to do with it.) And second, read, read, read—more, more, more. Take notes on what you read. Read like a writer, examining how certain effects are created. Look for clunky sentences and for clichés, so that you might avoid them in your own work. Risk becoming a snob by reading ever more difficult and artful work. And always keep in mind the books that you LOVE, those that rekindle your desire to be a writer. Keep them in a journal somewhere, along with sentences, paragraphs, beginnings and endings that inspire you. In those books you will find a pattern for what will work for you. And you’ll start putting your own sentences in that journal.

And when you do get the chance to publish, do whatever sad bullshit is required of you (I’m looking at you, social media) but don’t get caught up in that side of it, or caught up in the results or sales or any of that side stuff. NEVER confuse the bullshit for the art. You are a writer. That’s the only part that matters.

~*~*~*~

Jess, thank you for your time, and thoughts, and willingness to share. You are an inspiration and your books are excellent learning tools for writers everywhere.

Jess Walter Books:

So Far Gone (2025) Recommended 2025 Summer Reads: New York Times, Washington Post, CBS Sunday Morning, Los Angeles Times, Publishers Weekly, Indie Next and many more

The Angel of Rome (2022) “Intensely affecting fiction … The stories in ‘The Angel of Rome’ are largehearted and wonderfully inventive.” Hilma Wolitzer, The New York Times Book Review

The Cold Millions (2020) National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) Big Read and Washington State Book Award

We Live in Water (2013) Listed by former U.S. President Barack Obama on his best books of 2019 and longlisted for the Story Prize and the Frank O’Connor Short Story Award.

Beautiful Ruins (2012) #1 New York Times bestseller and spent more than a year on the bestseller list. It was also Esquire’s Book of the Year and NPR Fresh Air’s Novel of the Year.

The Financial Lives of the Poets (2009) Time Magazine’s#2 novel of the year

The Zero (2006) National Book Award Finalist

Citizen Vince (2005) Edgar Award Winner

Land of the Blind (2003) “Funny, philosophical and original.” The London Times

Over Tumbled Graves (2001) “Riveting … outstanding … tremendous emotional impact.” Washington Post Book World

Ruby Ridge (1995) Originally released as Every Knee Shall Bow Finalist for PEN/USA Award in nonfiction

- A Conversation with New York Times Best-selling Author: Jess Walter - October 8, 2025

- Get Inspired and Find Your People: Attend a Writers Conference - July 14, 2025

- There’s a New Podcast in Town… - June 13, 2025

Sign up to our newsletter to receive new articles and events.