Let’s See How It Works

As a writer, I’m always keen to dissect a story to see how it works. More than that, I want to pinpoint the difference between a great story and a world-class story, the kind that’s anthologized and taught for generations. Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” is such a story. If you’ve never read it, I beg you to do so. You can find it here for free.

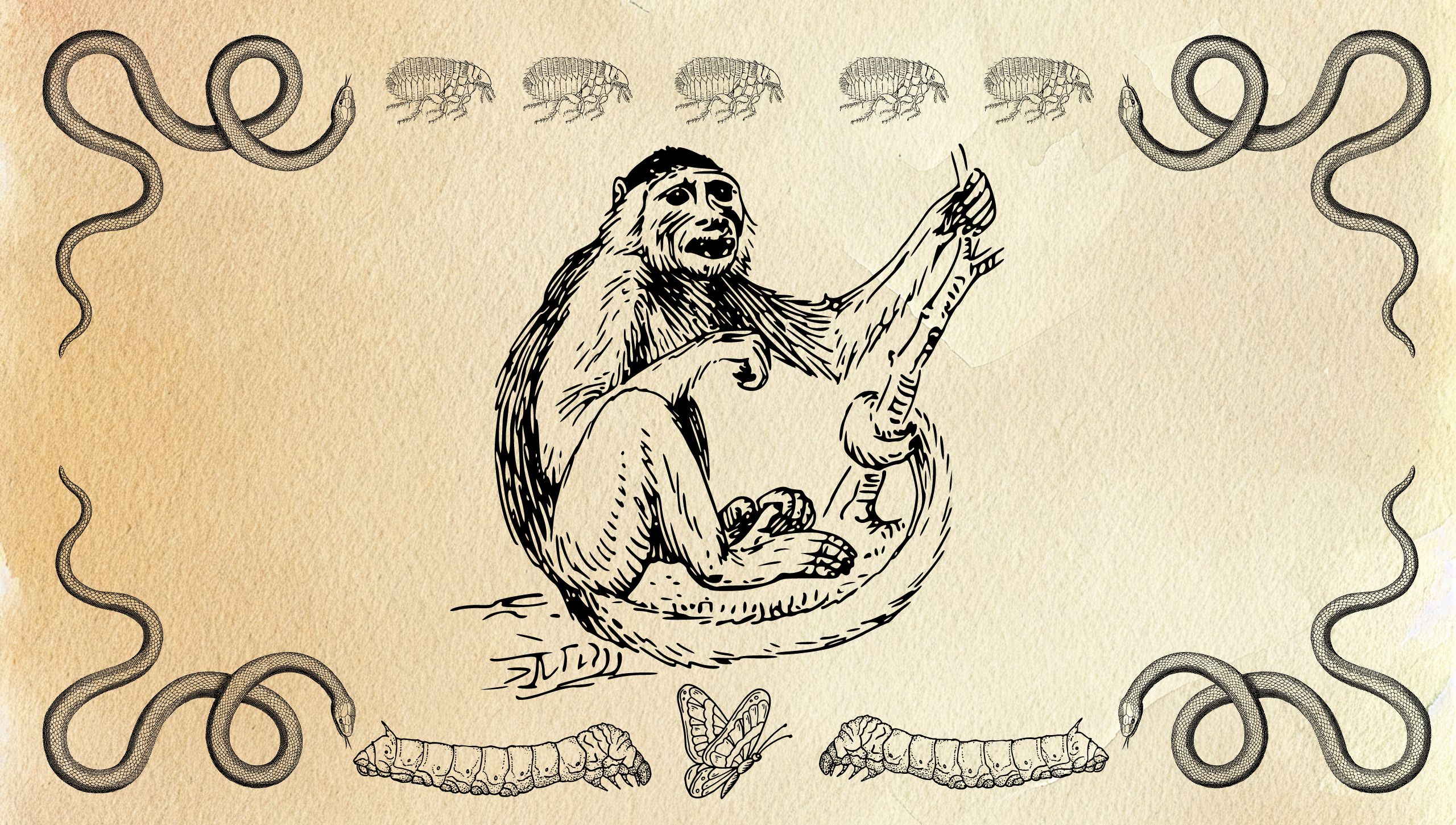

The premise of Flannery O’Connor’s 1955 story, “A Good Man Is Hard To Find” is deceptively simple. A Southern family embarks on a road-trip vacation to Florida and encounters a serial killer named The Misfit who brutally murders them. Beneath the surface of the story, however, nothing less than the immortal battle between Heaven and Hell is taking place. To point the reader to the eternal struggle, O’Connor embeds symbols in the text like breadcrumbs. The symbols are a series of animals hidden in plain sight as character descriptors. There are fourteen in all: dragon, rabbit, hippo, cat, cow, monkey, flea, horse, caterpillar, parrot, pig, dog, turkey, and snake. The animal symbols represent the bestial natures of the characters, but they also function in a special relationship to one another. Together, the trail of symbols and how they interact with one another weaves a breathtaking pattern that takes the reader into the soul of the story.

On the simplest level, animal symbols insinuate the personalities of most of the characters. The protagonist’s son, Bailey, for example, wears “a yellow sport shirt with bright blue parrots designed in it” (637). He is equated with the bird because, like a parrot, Bailey mimics the actions of a good son and father. Society approves and applauds a son who respects his parents. We quickly realize it’s a pretense, however, when Bailey’s first action is to ignore his mother: “Bailey didn’t look up from his reading” (631). And later, he “said something to his mother that shocked even the children…and The Misfit reddened” (638). Whatever it was, it was disrespectful enough to embarrass a serial killer. Bailey’s parenting skills are no better. His son, John Wesley, throws a tantrum and “kick[s] the back of the seat so hard that his father could feel the blows in his kidney” (636). Instead of correcting him, Bailey acquiesces. It’s a foreshadowing of the encounter with the Misfit when he does nothing to resist or protect his family. Like a parrot who imitates what it sees, Bailey is a character who only mimics manhood.

Bailey’s unnamed wife is “a young woman in slacks, whose face was as broad and innocent as a cabbage and was tied around with a green head-kerchief that had two points on the top like rabbit’s ears” (631). Beside making an excellent meal in some parts of the world, the rabbit is a prolific breeder. When confronted with danger, its instinct is to freeze. All three of these conditions mirror the mother of Bailey’s three children. After Bailey and John Wesley are murdered in the woods, she takes no action to protect her remaining family. In fact, she thanks the Misfit politely when asked if she would care to join her husband and son, docile rabbit that she is.

The couple’s two elder children share their association with the same creature: “John Wesley took [a cloud] the shape of a cow and June Star guessed a cow…” (633). The cow is a traditional animal of sacrifice. And for anyone who has ever owned one, it’s also gregarious and temperamental. For the grandmother’s part, she calls out in anguish for her murdered son, “like a parched old turkey hen crying for water” (641). The association with the turkey is unflattering, but paired with the lack of water, the description demonstrates both an irrelevance, and a lack of something required to sustain life. Interestingly, the only person in the family not to have an appointed animal is the infant. He’s simply too young to have developed any bad habits. The animals assigned to the individuals of the family imply each of their baser natures, and create an unsavory impression. Taken as a whole, this character-family’s symbols are mindless and domesticated, prey animals easily led to slaughter.

If the Grandmother’s family is a motley herd of prey, the animal symbols assigned to the Misfit’s family point to something untamed and sinister. Bobby Lee wears “a red sweatshirt with a silver stallion embossed on the front” (637). Unlike the domesticated horse, a stallion conjures the image of a wild rearing, kicking beast, unbroken by man. Living outside the laws of society as he does, it’s a fitting comparison.

Each of the Misfit’s multiple animal associations are worse than the next. He says: “My daddy said I was a different breed of dog from my brothers and sisters” (639). The dog was one of the earliest domesticated animals, the fast and faithful friend of mankind for millennia, but the Misfit isn’t that kind of dog. He was born with a rabid nature. A later association indicates just what a different breed he is. When touched by the grandmother, the Misfit “sprang back as if a snake had bitten him” (642). The snake, an ancient symbol of Satan, appears in the Garden of Eden to usher in the death of mankind. In another instance, the Misfit acts like an animal when “his voice had become almost a snarl” (642). Which animal is it? His preoccupation with Jesus points to the bible for an answer: “And the great dragon was thrown down, the serpent of old who is called the devil and Satan, who deceives the whole world…” (Zondervan New American Study Bible, Revelation 12:9). The snake and the dragon are one and the same creature, and so is the Misfit. At the story’s opening, there is an animal without an overt assignation: “The dragon is by the side of the road, watching those who pass. Beware lest he devour you” (631). Devour the family by the side of the road is precisely what the Misfit does.

As though these three animal associations are not damning enough, a fourth animal of the story’s menagerie belongs to the Misfit as well. At Red Sammy’s barbecue joint, “a gray monkey about a foot high, chained to a small chinaberry tree, chattered nearby” (634). The chinaberry tree is a symbol of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in the Garden of Eden (Thornton and Harvey, par. 13). In Genesis, the animal who sits in that tree is the snake. Here, the animal who sits in the tree is the monkey, also a common symbol of the devil (Thornton, par. 3). The switch is important. It serves the story’s message of redemption, which will be discussed shortly.

And what of Hiram, the final member of the Misfit’s unholy trinity of a family? Like the infant, Hiram does not have a direct animal association as the other characters do. Unlike the infant, it is not because of his inherent innocence. Hiram is an altogether different creature, like the Misfit, an unnamed animal of the menagerie. We come to know what Hiram is through the grandmother’s observations of the Misfit. When the grandmother and the Misfit meet, the Misfit “squatted down on the ground” (638), making her temporarily taller. “The grandmother noticed how thin his shoulder blades were just behind his hat because she was standing up looking down at him. ‘Do you ever pray?’ she asked. He shook his head. All she saw was the black hat wiggle between his shoulder blades” (640). In picturing the Misfit from her vantage, the brim of his hat forms a black halo. The Misfit’s shoulders, mentioned no fewer than eight times, are the remaining stubs of his lost wings. He is the fallen angel, Satan. Hiram, then, who wore “a gray hat pulled very low, hiding most of his face” (637) is also an animal with a halo, albeit gray–a shade lighter and less tarnished–to represent his nature as one of the legion of celestial creatures cast out of heaven.

To this point, we’ve encountered mammals, reptiles, and spirit animals that are directly associated with a character. The final class of creature present in the narrative is the humble insect–the caterpillar and the flea–and their associations behave differently than the others. The two have a unique, indirect relationship with the grandmother and the Misfit that serves a special purpose: to indicate the possibility of redemption. Unlike the other creatures of the menagerie, the insects are associated first with an animal, not a human, character. Pitty-Sing the cat “clung…like a caterpillar” (636). Pitty-Sing not only belongs to the grandmother, but is associated as an animal symbol to her as well because she “took cat naps” (635). Together, the cat, caterpillar and grandmother form a trio with a unique relationship. In mathematics, the relationship is called the Transitive Property of Equality. If A=B, and B=C, then A=C. In our context it equates to: If the grandmother=Pitty-Sing, and Pitty-Sing=caterpillar, then grandmother=caterpillar. The three of them have a transitive relationship where the Grandmother takes on an association with the caterpillar through Pitty-Sing. A second trio is formed by the Misfit, the monkey, and the fleas. We established earlier that the Misfit is associated with the monkey in the chinaberry tree. The monkey, in turn, is “busy catching fleas on himself and biting each one” (635). Thus we have: if Misfit=monkey, and monkey=fleas, then Misfit=fleas. The transitive natures of the symbols goes directly to the soul of the story.

Both the caterpillar and the flea share an extraordinary characteristic. They experience complete metamorphosis in their life cycles, beginning as one creature, and emerging as another, (Dr. Biology, pars. 1-5). No other animal in the story is capable of that. It’s a feature that has symbolic and far reaching implications for the grandmother and the Misfit. The only two characters to be associated with animals that change are also the only two characters in the story who experience any change themselves. The Grandmother has an epiphany immediately preceding death. In her final moments, all earlier vanity and selfishness fall away when she recognizes a common humanity with, and a kind of responsibility for, the Misfit. She says, “Why you’re one of my babies. You’re one of my own children” (642). The Misfit voices a change too. At first, he states that there is “no pleasure but meanness” (642) and after the Grandmother’s transformation, he says that meanness is “no real pleasure in life” (642). In a matter of several paragraphs, his words are quite literally reversed. He too, in some small way, is transformed. Sinners, and even the damned themselves, have the capacity to transmute, and it is symbolized by their transitive relationships with metamorphosing insects.

It’s a complicated structure, and begs the question: why? Could O’Connor not have achieved the same message, and made it more accessible to the reader, by simply using direct insect-human associations like she did with the animals and human characters throughout the narrative? Perhaps, but something would be lost. By using a symbolic intermediary, a connector, between the character-sinner of the beginning and the character-transformed of the ending, O’Connor creates a bridge between two pillars. The very structure of the transitive relationships embodies metamorphosis itself, mirroring that middle stage between the pillar of human-sinner on one side and human-redeemed on the other.

The menagerie of animal symbols in Flannery O’Connor’s story serve on the surface as simple, unflattering descriptors of the individual characters and their capacities for lesser and greater evils. Look a level deeper, and the symbols can be divided into natural groups of prey and predator that hint at the larger movements of the story. Dig deeper still, and see that one animal in each of the opposing groups is an insect, arguably the smallest, and therefore meekest, class of creatures on earth. Despite the opposition of their two camps, the two insects share a unique ability. They alone among the animals are capable of complete transformation, starting as one creature and becoming a different creature altogether by the end of their respective life cycles. It is this unique ability to transform that offers a message of hope in an otherwise violent and depressing story.

Consider also that the animal symbols number fourteen, despite the presence of only twelve characters. The number fourteen is significant. First, it “represents deliverance or salvation…in the Bible” (Biblestudy.org, par. 5). Second, the fourteen animals are perfectly balanced by the fourteen human heads noted in the story, four of the instances on the first page: Bailey’s “bald head” (631), June Star’s “yellow head” (631), the mother’s “head-kerchief” (631), and the family “headed to Florida” (631). It is a deliberate comparison, a counterweight to the animal instinct. Man can embrace his baser, animal nature or he can exercise his head and mind instead. He has been given a divine gift by God—the right to think, to choose. With faith the size of a mustard seed, or of a caterpillar or flea, mankind’s tendency to the animal can be transformed by Free Will, God’s greatest gift to humanity. O’Connor subtly insists with her symbolism that Mankind can choose the road, not to the dragon, but to redemption.

Works Cited

“Chinaberry Tree Uses and Other Facts.” Gardenerdy, par. 13, gardenerdy.com/chinaberry-tree-uses-other-facts. Accessed 2 Apr 2018.

Dr. Biology. “Complete Metamorphosis.” Arizona State U, 29 Apr 2011, pars. 1-5 askabiologist.asu.edu/complete-metamorphosis. Accessed 31 Mar 2018.

The Holy Bible, Zondervan New American Standard Study Bible. Grand Rapids, Zondervan House, 1995.

“Meaning of Numbers in the Bible/The Number 14.” Biblestudy.org, 2014, par.13. biblestudy.org/bibleref/meaning-of-numbers-in-bible/14.html. Accessed 16 Apr 2018.

O’Connor, Flannery. “A Good Man Is Hard to Find.” The Story and Its Writer: An Introduction to Short Fiction. 5th ed., Edited by Ann Charters, Boston, Bedford/St. Martins, 1999, pp. 631-642.

Thornton, Alicia and Suzanne Harvey. “Where the Wild Things Are: 15th Century Christian Art…?” UCL, 3 Sep 2012, par. 3. blogs.ucl.ac.uk/researchers-in-museums/2012/09/03/where-the-wild-things- are-15th-century-christian-art/. Accessed 2 Apr 2018.

- 5 Important Craft Books Every Memoir Writer Needs - September 25, 2025

- 3 Steps to Hook the Heart of Your Reader: Advice From Brandon Sanderson - June 6, 2025

- Writer on the Road - February 6, 2025

Sign up to our newsletter to receive new articles and events.